The first white family to take

up residence in the immediate vicinity of Abilene was that of Timothy F. Hersey

in 1856. He staked out a claim on the west bank of Mud creek about two miles

north of where it empties into the Smoky Hill river.

Hersey Cabin ctsy oldabilenetown.org

When the Butterfield

Overland Despatch stage line was being formed at the end of the Civil War, he was

given a contract to provide a home station. He provided two log houses and a

log stable and corral for horses. He agreed to feed the passengers and

employees who came over the trail in the six-horse Concord coaches. Part of his

advertisement to west-bound travelers was they would find at his station the

"last square meal east of Denver." Food at some of these stations

consisted of bacon and eggs, hot biscuits, green tea, coffee, dried peaches and

apples, and pies. Beef was served occasionally, as were canned fruits and

vegetables.

The next building in the area was a dwelling known as "the Hotel," owned by C. H.

Thompson. It was located opposite Hersey’s station on the east bank of Mud Creek. Thompson also used his business as a way station for the Short Line

Stage Company.

In 1864, a city block east from the

creek, W. S. Moon built the Frontier Store. In it, he offered for sale a small

stock of widely assorted general merchandise. Mr. Moon also served as the postmaster

and register of deeds. His store later served as a meeting place for the

sessions of district court.

Prairie Dog Town near Abilene, Kansas - 1867

Away

from the trail and in the midst of a prairie dog town was "Old Man Jones'

" saloon . Over the years, as emigrants followed the Smoky Hill Trail west,

some were attracted by the rich growth of prairie grass on the Smoky Hill river

bottom land. They decided to go no farther. From these settlers, about a dozen

scattered log houses sprang up on the east side of the creek.

(On this 1859 Kansas map, Dickinson County is outlined in blue) In 1860, the counties of Kansas foresaw

coming statehood for the territory, and the momentum to organize grew. The

community along Mud Creek was part of Dickinson County. The residents

recognized the value of living in the county seat. However, to have a chance

against the other communities in the county, they knew they had work to do. C.

H. Thompson laid out a townsite on his land east of Mud creek. He quickly

constructed several makeshift log houses to give it some semblance of a town.

The community needed a name. Mr.

Thompson went to the first inhabitant, Tim Hersey, and asked him to give the

new town a name. Mr. Hersey turned the issue over to his wife. Mrs. Hersey

found a reference in the first verse of the third chapter of Luke in the Holy

Bible which spoke of the "tetrarch of Abilene." She "Abilene,"

which meant "city of the plains," would be appropriate name, and the

decision was made.

A

county-seat election was held in the spring of 1861. Union City, Smoky Hill

(now Detroit), Newport, and Abilene were all contenders. Abilene, by securing

the support of the Chapman creek settlers, won the election.

There is very little recorded of the

events in Abilene from 1861 to the coming of the railroad in 1867. No doubt its

development during this period was much the same as other Western frontier

towns during the Civil War period. The town was rustic—still comprised mainly

of log buildings. There were no streets. Spaces between the houses were overgrown

with prairie grass. The frontier stores were cluttered and dirty, which created

a problem in sanitation.

The arrival of a stage or the passing

of an emigrant party down the trail brought out the whole populace to find out

who was aboard, whence they came, and whither bound, eager for any bit of

rehashed or revised news from some other point. Eastbound travelers brought

news of some late Indian depredation, and those who were westbound brought word

of some more or less recent happening of the war which was then in progress.

The summers brought out the loiterers. The winters were largely open and

agreeable, but there were frequent bleak winds and occasional blizzards. The

hunting expeditions after buffalo, antelope, wild turkey, and prairie chicken

served the double purpose of providing a diversion and a source of meat.

Loading cattle on the Kansas Pacific in Abilene - 1867

This

was the Abilene that Joseph G. McCoy found when he came west on the Kansas

Pacific railway in 1867 in search of a spot on that line which could be used as a

shipping point for the herds of Texas cattle being driven north. He wrote:

“Abilene in 1867 was a very small, dead

place, consisting of about one dozen log huts, low, small, rude affairs,

four-fifths of which were covered with dirt for roofing; indeed, but one

shingle roof could be seen in the whole city. The business of the burg was

conducted in two small rooms, mere log huts, and of course the inevitable

saloon, also in a log hut, was to be found.”

Drovers Hotel - 1867

That

same year, Joseph G. McCoy bought 250 acres of land north and east of the town.

On his land, he built a hotel, the Drovers Cottage (also known as Drover’s

Cottage, although the name painted on the side of the building did not include

an apostrophe).

Mr.

McCoy also built stockyards large enough to hold 2,000 heads of cattle and a

stable for the drover’s horses. The Kansas Pacific put in a switch at Abilene

that enabled the cattle cars to be loaded and sent on to their destinations. He

encouraged Texas cattlemen to drive their herds to his stockyards.

The first twenty carloads left

September 5, 1867, en route to Chicago, Illinois. McCoy being familiar with the

meat market. The stockyards shipped 35,000 head that first year.

From there, the town grew quickly and

became the first cow town of the West. It became the largest stockyards west of

Kansas City, Kansas.

1873 Chisholm Trail

The herds of cattle were driven from

Texas north on the Chisholm Trail. From 1867 to 1871, the north end of the

trail ended in Abilene. Abilene became the largest stockyard and cattle

shipping point west of Kansas City, Kansas. The Chisholm Trail also brought

other travelers, which made Abilene one of the wildest towns in the West.

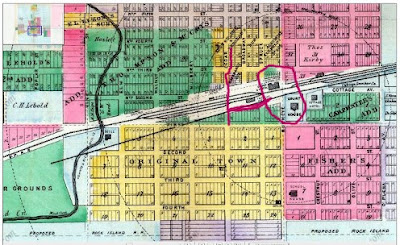

(This 1887 Map of Abilene shows a more-developed town that what existed in 1867-71. The black wavy line on the left is Mud Creek. The vertical red line shows Cedar Street, the section north of the tracks not being very developed and the saloon district being south of the tracks . Texas Street ran parallel to the railroad tracks. The circle shows the general area of the Drovers Cottage on the south of the tracks and the stockyard on the north of the tracks.)

At first, the section of Abilene along

Cedar and Texas Streets that catered to the Texas cowboys had no law

enforcement, to speak of. The more stable residents of the original town of

Abilene did not consider it their problem. However, by 1869, it became apparent

to

the law-abiding citizens that municipal organization was necessary to bring

order to the unruly blocks east of their city in order for the violence not to

spill over and disrupt their lives. On September 3, I869, a group of citizens

bearing a petition signed by forty-three citizens appeared before the court of

Cyrus Kilgore, probate judge of Dickinson County, Kansas, "praying for

incorporation." The petition was granted, and the citizens chose a group

of trustees to manage the city until elections could be held.

This took

place toward the end of the 1869 cattle season. Other than pass a few basic

ordinance, the town did little as far as enforcing law and order.

In the spring

of 1870, the board of trustees met again. Thirty-two saloons were licensed,

closing hours were established, houses of ill-fame in the city limits were

outlawed, and an attempt was made to recognize and enforce laws against the

more serious crimes. City offices, including the city marshal position, were

created. Ordinances were published.

Next month, my post will be about law

enforcement in Abilene during the days of the cattle drives.

On April 3, I871, the

first charter election was held to elect a mayor and council. J. G. McCoy, the

cattle magnate in Abilene, was elected mayor. The main issue in the election

revolved around the degree of control that should be attempted over the vice

and immorality brought into Abilene by the Texas cattle trade.

Joseph McCoy

On May 1,

1871, a comprehensive plan of licensing all business houses in Abilene was

included in an ordinance by the city council. This was an attempt to force the

transient businesses that catered to and thrived from the Texas cattle trade to

help defray the high cost of law enforcement. The city council became

deadlocked over the amount of the fee they should charge, which led to several

disputes among them.

In 1871, more than 5,000 cowboys herded

between 600,000 and 700,000 cows through town. However, other forces in the

town and county would soon spell the end for this as a cattle shipping point.

Farmers, who had homesteaded the land

around Abilene and who were a more stable, year-round population, opposed the

Texas Longhorns from entering Dickenson County. The Longhorns brought with them

a tick that was deadly to their domestic cattle. Increasingly, they began to

dominate the politics. In February 1872, a petition was circulated and signed

by about 80% of the population who wanted an end, not only to the dangers of

the tick infestation, but to the evils brought by the Texas cowboys and the

saloons, gamblers, and prostitutes who catered to them. They were requested to

take their cattle elsewhere.

McCoy could see the writing on the

wall. Although in 1872, it was the town of Ellsworth who enjoyed being the

biggest Texas cattle drive destination, Mr. McCoy dismantled his Drovers

Cottage and rebuilt it in the town of Newton, which became the preferred

destination after Ellsworth.

Abilene did not die with the loss of

the cattle trade. The agriculture trade grew and stabilized the town. However,

its days as a rowdy and lawless cow town were at an end.

I included Abilene, Kansas, in several of my books.

In Mail Order Lorena, the time period

is 1865-66 and the setting is primarily the Butterfield

Overland Despatch stage station in Ellsworth, Kansas. However, my hero often

rides the stagecoach east to stay at the station in Abilene and spend time in a

fictional town saloon, where he meets Lorena. You may find the book description

and link by CLICKING HERE.

In Otto’s Offer, in 1868, Otto Atwell was among those farmers who homesteaded land

just outside of Abilene. Although not part of this book’s plot, he would have been among

those who opposed the Texas cowboys bringing up the long horn cattle that were host to the ticks that brought deadly disease to domestic cattle. You may find the book description and link by CLICKING HERE.

My most recent book, Abilene Gamble, is set in the summer

of 1871 Abilene, after the town has experienced a great deal of growth and

settlement. As a lawyer and investigator/bounty hunter who carries the scars

from his time fighting in the Civil War, my hero, Harry Bradford, found his

niche in this rough-and-tumble town. You

may find the book description and link by CLICKING

HERE. (Much of this blog post was taken from the Author Notes at the back

of this book.)

Sources:

https://abilenekansas.org/abilenes-history

https://oldabilenetown.org/tim-hersey

https://www.kshs.org/p/abilene-first-of-the-kansas-cow-towns/12833

https://abilenekansas.org/blog/2019/12/18/area-history

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abilene,_Kansas