I'm resharing blog post I wrote two years ago after an early October blizzard decimated the cattle herds out West.

I’m a weather watcher. This winter is seemingly starting early, starting out viciously and unseasonably cold (it’s ONLY mid-November!), and appears to be headed to another long, cold, and snowy winter, thanks to “polar vortices” and “above average precipitation” and “la nina” (or is it el nino?).

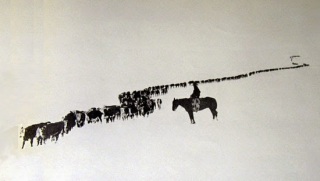

When I was a kid, we used to call this kind of weather “winter.” Last winter started out much the same and it was devastating for the cattle industry in places like Wyoming, the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, and Iowa. Because the snow came very early, the cattle hadn’t put on their winter coats, and the snow was followed by the first, hard blast of the polar vortex, many ranchers lost a considerable number of head to hypothermia. It wasn’t that the ranchers don’t do all they can to help their herds survive the winter with hay feeding and by moving them down into lower pastures in the late fall or that the cattle couldn’t handle the cold and the snow under normal conditions—it was that “normal” wasn’t in play in fall and early winter last year.

Last winter and this year’s early arrival of winter make those of us who are Western history buffs think of the “Great Die-Up” on the Western Plains in the winter of 1886-87. The losses that winter were staggering and ruined many ranches. “Normal” wasn’t in play that winter, either.

The winter of 1886-87 came on the heels on one of the worst droughts that the settlers and ranchers on the Great Plains had seen in their limited time there. Prior to that winter, for many years of the preceding three decades of settlement, rainfall in a usually semi-arid land had been well above normal, creating lush landscapes on which to graze cattle. After the American Civil War, land was basically free for the taking under the Homestead Act and the land they grazed their cattle on was owned by no one so these cattlemen established codes to govern the West and to protect it from outsiders. Principal among such codes was the Law of the Open Range, the unwritten rule of free access to grass and water. Most did not own the land on which their cattle grazed, and thus the Law of the Open Range secured their rights, by warning farmer-pioneers “not to stand in the cowman’s route to the ranges, not to block his way with towns and fields–and of all things—fences.” The cattlemen had settled the West prior to the Civil War. It wasn’t until after the Civil War that their empire was built. After the Civil War the demand for beef reached unprecedented levels, driving the cattle to higher and higher values and more and more cattle were brought to graze the “free land” of the West.

Because of the railroads, that beef could be transported quickly and efficiently (either on the hoof or in rail cars specifically designed to transport meat kept cool with ice) to markets back East.

In the 1870s, barbed wire made its first appearance on the range, following the passage of The Homestead Act in the late 1860s. Now, smaller homesteaders could settle the Plains, keep their crops protected from ranging cattle and prevent access to water. The cattlemen were furious and range wars became the normal—but that’s a story for another day.

The rains dried up and the lush grasses that had first lured the cattlemen burnt in the summer sun. Two years of extreme drought was followed by one of the worst winters on record. The snows started in late October of 1886 and didn’t stop until the following May. There is a recorded period, from November 13, 1886 until December 24, that it snowed every single day. When it wasn’t snowing and would warm up to a few degrees above freezing, it rained. This rain created a cap of ice several inches thick on the snow cover. And when it would momentarily stop snowing or raining, the bitter cold would return.

In January of 1887, the blizzards came and with the blizzards came a kind of cold that locals call “freeze-eye cold”—a cold so intense and bitter it would freeze the moisture on eyelashes. Blizzards came howling over the plains, blasting the unsheltered herds. Some cattle, too weak to stand, were actually blown over. Others died frozen to the ground.

Starving cattle, already weakened by a lack of grazing fodder because of the drought, would attempt to paw through the ice and snow to what was left of the drought-blighted and sun-burnt grasses. “The cattle had the hair and hide wore off their legs to the knees and hocks. It was surely hell to see big four-year-old steers just able to stagger along” (Teddy Blue Abbott). The cattle would drift with the howling winds. Cattle won’t stop “drifting” until they run into an immovable object: a dead-end canyon, a rock face, a barbed wire fence. The results were horrific as one account states:

They moved “like grey ghosts” . . . icicles hanging from their muzzles, eyes, and ears,” directly into the fences. There they were stalled; they could not go forward, and they would not go back. They stood stacked together against the wire, without food, water, warmth or shelter. The pressed close against each other in groups all along the fence line, and sometimes they gathered in bunches reaching as much as four hundred yards back from the fence. Still there was not enough warmth in their huddled forms to counteract the cold, and within a short time they either smothered or froze in their tracks (Hill, J.L.. The End of the Cattle Trail. Austin, Texas: The Pemberton Press, 1969).

The spring thaw of 1887 (in late May) revealed the extent of the devastation. More than fifty percent of the cattle herds died that winter from hypothermia and starvation. Some ranches lost upwards of seventy-five percent of their livestock. Dead cattle were found everywhere, observed bobbing in the streams as the ice broke up, and discovered in large groups dying where they stood.

It was a perfect storm of conditions: decades of unusually high rainfall in a semi-arid land, overgrazed land, a severe drought that ended the wet period, too many cattle and the open range cut-up and sectioned off with barbed wire. The “Great Die-Up” as cattlemen called it in a dark attempt at humor marked the end of open range ranching, that supposedly sure way to riches which Theodore Roosevelt called “the pleasantest, healthiest and most exciting phase of American existence.” And it proved again that nature can at any moment shatter all sense of human control.

Hi Lynda:

ReplyDeleteGreat blog, and so sad. Heartbreaking just thinking about all those cows. When we have snow storms here in Colorado, especially on the eastern plains, I always hope for the best for the cows and the horses.