Windham

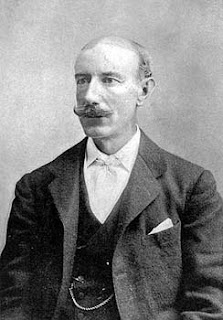

Thomas Wyndham-Quin, 4th Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl, an Anglo-Irish peer,

first viewed the Rockies in 1869, aged twenty-eight and on his honeymoon. He had

gone to Oxford and served in the Queen’s Life Guards. Best known for being a

journalist, writing articles on travel and hunting, he was generally considered

an enlightened and rather progressive man for his background, and mixed

socially with writers, actors and musicians. His boyhood had been spent reading

the western novels of Mayne Reid and Fenimore Cooper so that, despite having a

young bride in tow, he now aimed to travel west and hunt.

Circumstances

conspired against him that year, however, and his party reached only as far as

Denver. The dramatic backdrop to this burgeoning town was enough to enthrall

him. In the next sixteen years, Dunraven was to travel annually to the west,

sometimes more than once a year. After all, Denver was ‘only’ seventeen days

from Liverpool.

Estes Park had been home to Arapaho and Ute and occasional

Apaches. Trappers had passed through, and Missourian Joel Estes came in 1859 to

try his hand at ranching there. Griff Evans arrived in 1867 and built cabins to

accommodate tourists and lead hunting trips. In 1872, Dunraven finally set eyes

on the area for the first time.

He had inherited title just a year earlier, and

now commanded his family’s extensive fortune, including banks, railroads,

shipping and coal, as well as four mansions scattered throughout the British

Isles. Having hunted throughout the west on visits over the last three

years—including one hunt led by William Cody and his pal, Texas Jack— Dunraven

now stayed at one of Evans’ cabins for three weeks and subsequently set his

heart on having the park for his private hunting ground. The earl had caught

‘prairie fever’ as Mayne Reid had called it.

Why Dunraven favored Estes Park came down to several details, as

varied as the beautiful sunsets, the dry air, and the fact nearby Denver was a

station for no less than five railroad lines. He loved the area so much that he

paid Albert Bierstadt $15,000 for a painting of Estes Park, the first of many

he would take home to remind him of his place in Colorado. The way Dunraven set

about obtaining ownership to six thousand acres was a modus operandi that would

be employed by numerous ranchers throughout the west in the coming years.

Exercising his vast resources, he had his agents bribe various American

citizens to make use of both the Pre-emption Act and Homestead Act to either

buy or prove up 160 acres each. By choosing the sites wisely, Dunraven enclosed

more acreage without access to water. Thirty-one claims were filed for his use.

But such a land grab could not go unnoticed. Squatters moved in,

and a grand jury was set to investigate his claims. While none of this came to

anything, and Dunraven kept his land titles, the harassment showed him the

writing on the wall. He had the roads improved and built a hotel as well as a

sawmill. Back home in Britain, he was increasingly involved in politics, and

would later serve in Her Majesty Queen Victoria’s government under Lord

Salisbury, as well as in the Senate of the Irish Free State. The Earl made his

last visit to Estes Park in 1882, but it was not until 1908 that he sold his

land to F.O. Stanley and B. D. Sanborn. Stanley, of course, built the

now-historic Stanley Hotel. Rocky Mountain National Park was signed into being

in 1915.

It is a strange anomaly that a man who wrote approvingly about the

preservation of Yellowstone as a national park for the enjoyment of the general

public, and later would be instrumental in passing the Irish Land Purchase Act

of 1903 (permitting tenants to purchase land with favorable terms from their

landlords), should want to illegally secure such a large swathe of American

countryside for his own use. But Dunraven was very much a product of his background, if an

enlightened one, and only the first of many Brits who would seek to use the

west for their own profit and enjoyment.

An earlier version of this appeared 2015 at http://andreadowning.com

Photo of Lord Dunraven public domain; all other photos author's own

Interesting. I've never heard of him. That was a long way to travel year after year. Thanks for sharing, Andi!

ReplyDeleteLove the pictures! 17 days is a long trip from Liverpool, but not as long as I would have expected before air travel. I don't know how people had it in them to cover such distances--repeatedly in his case! But I guess he traveled first class so it may have been restful. I have heard of him but not in relation to Colorado, let alone an attempted land grab. I think you nailed it when said he was a product of his background: enlightened but entitled!

ReplyDeleteKristy, I certainly can't imagine traveling 17 days there and 17 back but it's amazing how many of them did it. Morton Frewen, a Brit who owned a ranch on the Powder River, made more than 100 crossings in his lifetime. When his wife arrived by train at Cheyenne and was told she still had another 200 miles to go before reaching the ranch, she burst into tears. She only made the one trip as far as I know!

ReplyDeletePatti, there is a Dunraven Pass in Yellowstone NP and probably other places named for him. I think his love for the area was genuine but, as you so wisely put it, enlightened but entitled. I guess when you're brought up that way and have so much money--think of paying Bierstadt 15K in those days!!--it's difficult to escape your background. But no excuse...

ReplyDeleteWe found Estes Park and the Rocky Mountain National Park on a ski trip, years ago, and you're right, it's truly beautiful country. Your pics show only a bit of how beautiful it is. I had also been there, during the summer, visiting a college roommate of mine who lived in Loveland, Co.

ReplyDeleteLord Dunraven's bid had quite an impact on the area, and like you said, it does seem surprising, considering his position on other land issues. It's a good thing he was stopped, especially for our country. Beautiful area!

He was not stopped. He sold out in 1908.

ReplyDelete