The discomfort of rail travel began at the station house or depot, often described as a sort of charming social center. The truth is that these depots were a favorite lounging spot for loafers and the homeless. Spittoons sat everywhere, lying in wait for some unsuspecting traveler to accidentally kick over. As in saloons, "spitters" often missed, so that almost as much spital covered the floors as filled the spittoon. The lack of "no smoking" areas meant the air was thick and gray with smoke from cigarettes and cigars.

There was no such thing as a "check system" for luggage, which had to be identified and retrieved by the passengers themselves. This resulted in frequent arguments and the occasional smashing of trunks and bags, not to mention theft. Not only did baggage handlers (called baggage-smashers) not care who owned which bag, they gave no thought to how they treated the luggage in their care.

Train schedules of the period left much to be desired. Connections were more miss than hit, partly because of competing railroads. A traveler from Woodstock, Vt. in 1888 took two days to get to New York City. The response to his inquiry about when a certain train would leave was "sometime." A journey of twenty-four miles could take two and a half hours.

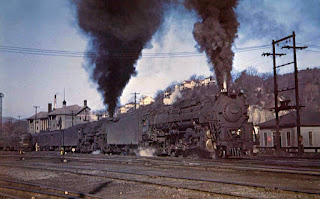

Train schedules of the period left much to be desired. Connections were more miss than hit, partly because of competing railroads. A traveler from Woodstock, Vt. in 1888 took two days to get to New York City. The response to his inquiry about when a certain train would leave was "sometime." A journey of twenty-four miles could take two and a half hours.The bulk of passenger traffic came from the middle class, but the conditions they endured came closer to matching emigrant carriages than private rail cars. The wood-burning locomotives belched cinders that pattered overhead like hail. Smoke and steam engulfed the train until, at journey's end, the traveler appeared as though he had labored in a blacksmith's shop all day.

Travelers could close the windows and instead suffer the stink of whiskey, tobacco, and closely packed bodies. That was if they could open poorly designed windows. Noise added to the discomfort, often drowning out all but the loudest of voices.

Travelers could close the windows and instead suffer the stink of whiskey, tobacco, and closely packed bodies. That was if they could open poorly designed windows. Noise added to the discomfort, often drowning out all but the loudest of voices.European trains offered small compartments to reduce noise and bodily discomfort, but American railroads herded sixty to seventy passengers into each long car. The backs of the seats were too low to act as headrests, and if a passenger managed to nap in spite of the noise, he was soon awakened by the "trainboy," a peddler of books, candy and sundry goods whose visitations were constant and disruptive. Mark Twain on his way West was badgered by what he called their "malignant outrages." He also noted that passengers looked "fearfully unhappy...doubled up in uncomfortable attitudes, on short seats in the dim funereal light...like so many corpses who had died of care and weariness."

Pullman's self-contained sleeping car, introduced in the late 1860s, was considered a milestone in transportation luxury. Getting dressed in one, it was said, could only be accomplished if the person were expert at dressing under a sofa. Bad air trapped behind heavy curtains, the jolting of the train, and the overall cacophony of snores and crying babies made sleep nearly impossible.

Pullman's self-contained sleeping car, introduced in the late 1860s, was considered a milestone in transportation luxury. Getting dressed in one, it was said, could only be accomplished if the person were expert at dressing under a sofa. Bad air trapped behind heavy curtains, the jolting of the train, and the overall cacophony of snores and crying babies made sleep nearly impossible.Food on board was up to the passengers, who brought with them baskets and containers loaded with whatever suited their fancy. One prominent odor in rail cars came from cabbage cooked over the stoves provided for heat. The Pullman dining car, when it came along, sounded like heaven but received few rave reviews from visitors of the times. Few travels could afford to eat in such cars. Most gobbled down quick, greasy meals at lunchrooms along the line. Stops for such meals lasted all of five or, if you were lucky, ten minutes to order, receive and eat your food.

Add to this the fact that train wrecks due to broken trestles, poor track, exploding boilers, faulty signals, and careless engineers and switchmen were a daily occurrence, producing an accident rate in the US five times that of England. In 1890 railroad-connected accidents caused 10,000 deaths and 80,000 serious injuries.

All in all, it doesn't sound like the most pleasant method of travel, but at least, it was over much sooner than wagon trains or ocean travel. I am very thankful I live today with safety regulations, automobiles, and airplanes.

4 comments:

Really interesting post, Charlene. I'm old enough to remember those sleeper cars--though not in the 1890s, I hasten to add, but very similar to what you describe. The porter would come around and pull them down from the ceiling and convert them into two separate beds. The space in them was so narrow that, yes, you had to be lying flat to get your clothes on and off rather like dressing under a couch as you said. The summer camp I was sent to had us arrive in those days via overnight train so that's when I experienced this.

The hero and heroine in my latest WIP are about to embark on a train ride so this post was perfect timing for me! Thanks so much for making my research easier! Great post!

My characters are always complaining about the state of train travel whenever they have to go anywhere. They have to endure the long, noisy ride and they arrive covered in cinders and ash. Exactly as you've described - still, it beat the stagecoach!

Thanks for sharing this information. I really like your blog post very much. You have really shared a informative and interesting blog post with people.. pnr status

Post a Comment