Who

better to honor this Memorial Weekend than Audie Murphy? Through LIFE

magazine's July 16, 1945 issue ("Most Decorated Soldier"/cover

photo), Audie Leon Murphy became one the most famous soldiers of World War II

and widely regarded as the most decorated American soldier of the war. After

the war he became a celebrated movie star for over two decades, appearing in 44

films. He later had success as a country music composer. And how appropriate

that we honor him this weekend. In addition to be America’s Most Decorated

Soldier, Audie Murphy died in a plane crash on Memorial Day Weekend, May 28,

1971.

|

| Audie Murphy Official Portrait with Medals |

Audie

Leon Murphy was born to sharecroppers near the community of Kingston in Hunt

County, Texas. His parents were of Irish descent, Emmett Berry Murphy (February

20, 1886–September 20, 1976), and his wife, Josie Bell (née Killian

(1891–1941). He grew up on farms in Hunt County and has several memorials

there. He was the sixth of twelve children, two of whom died before reaching

adulthood.

In

1933, Emmett and Josie Murphy with their 5 children June, Audie, Richard, Gene,

and Nadine moved to Celeste, Texas with the primary purpose of enrolling the

children in school. They lived in an abandoned railroad boxcar on the southern

end of the small community for several months before renting a rundown home in

Celeste until 1937. The railroad car no longer exists.

|

| Audie Murphy as a boy |

While

the family lived in Celeste, the two remaining Murphy children, Beatrice and

Joseph, were born. It was here that Audie befriended the Cawthon family who

played a prominent role in his life. In 1937, the Murphy family moved back into

the abandoned railroad car for several weeks and then moved to a farm near

Floyd, Texas located just west of Greenville. Audie finally moved out on his

own in 1939 at the age of 15 after finding a job with Haney Lee, who had a farm

nearby

Audie

Murphy spent a lot of time with his grandparents, Jefferson D. and Sarah

Elizabeth Killian, at their hope in Farmersville, Texas. In fact, the Killian’s

was a place of refuge for the Murphy children when times were difficult during

the years of the depression. At the height of the depression, around 1929 or

1930, Audie's oldest sister, Corrine, left the Murphy family and moved in with

the grandparents in their Farmersville home to help relieve some of the

financial stress burdening the Murphy family.

As

the family moved from community to community over the years, they never strayed

too far from the Killian home. Around 1933-36 (depending on the account),

Emmett Murphy, who was known to disappear for weeks at a time while apparently

seeking employment, finally vanished permanently. He had attempted to convince

his wife and family to move with him to West Texas where he hoped to find work

in the oil fields. Unconvinced that this was a wise move, Mrs. Murphy did not

want to leave the area where her parents and lifelong friends lived.

At

the time of their mother's death, Audie was approximately 17 years old and was

declared by the county to be old enough to take care of himself. The placement

of his siblings in the Boles Childrens Home in Quinlan was an event that Audie

vowed to correct. On more than one occasion during the war, he told his buddies

that he hoped to someday earn enough money to reunite what remained of his

family. As it turned out, Audie was able to keep his promise.

Audie

attended elementary school in Celeste, Texas until his father abandoned the

family. Audie dropped out to help support the family. He

worked for one dollar per day, plowing and picking cotton on any farm that

would hire him. Murphy became very skilled with a rifle, hunting small game

like squirrels, rabbits, and birds to help feed the family.

One

of his favorite hunting companions was neighbor Dial Henley. When Henley

commented that Murphy never missed what he shot at, Murphy replied, "Well,

Dial, if I don't hit what I shoot at, my family won't eat today."

On

May 23, 1941, his mother died. He worked at a combination general store, garage

and gas station in Greenville. Boarded out, he worked in a radio repair shop.

Later that year, with the approval of his older, married sister, Mrs. Elizabeth

Corinne Burns (usually referred to as "Corrine"), who was unable to

help, Murphy placed his three youngest siblings in an orphanage to ensure their

care. He reclaimed them after World War II.

He

had long dreamed of joining the military. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on

December 7, 1941, Murphy tried to enlist in the military, but the services

rejected him because he was underage. In June 1942, shortly after what he and

his sister Corrine believed was his 17th birthday, Corrine adjusted his birth

date so he appeared to be 18 and legally able to enlist. His war memoirs, TO

HELL AND BACK, maintained this misinformation, leading to later confusion and

contradictory statements about his year of birth.

Murphy

was small, only 5 ft 5 inch and 110 pounds, but he tried once again to enlist

and was declined by both the Marines and Army paratroopers as too short and

underweight. The Navy also turned him down for being underweight. The United

States Army finally accepted him and he was inducted at (some reports say

Dallas) Greenville, Texas and sent to Camp Wolters near Mineral Wells, Texas

for basic training. During a session of close order drill, he passed out. His

company commander tried to have him transferred to a cook and bakers' school

but Murphy insisted on becoming a combat soldier, and after 13 weeks of basic

training, he was sent to Fort Meade, Maryland for advanced infantry training.

Murphy

was awarded 33 U.S. decorations and medals, five medals from France, and one

from Belgium. He received every U.S. decoration for valor available to Army

ground personnel at the time. He earned the Silver Star twice in three days,

two Bronze Star Medals, three Purple Hearts, the Distinguished Service Cross,

and the Medal of Honor.

After

seeing the young hero's photo on the cover of the July 16 edition of Life

Magazine and sensing star potential, actor James Cagney invited Murphy to

Hollywood in September 1945. Despite Cagney's expectations, the next few years

in California were difficult for Murphy. He became disillusioned by the lack of

work, was frequently broke, and slept on the floor of a gymnasium owned by his

friend Terry Hunt. He eventually received token acting parts in the 1948 films

“Beyond Glory” and “Texas, Brooklyn and Heaven.” His third movie, “Bad Boy,”

gave him his first leading role.

He

also starred in the 1951 adaptation of Stephen Crane's Civil War novel, “The

Red Badge of Courage,” which earned critical success. Murphy expressed great

discomfort in playing himself in “To Hell and Back.” In 1959, he starred in the

western “No Name on the Bullet,” in which his performance was well-received

despite being cast as the villain, a professional killer who managed to stay

within the law.

After

returning home from World War II, Murphy bought a house in Farmersville, Texas

for his oldest sister Corrine, her husband Poland Burns, and their three

children. His three youngest siblings, Nadine, Billie, and Joe, had been living

in an orphanage since Murphy's mother's death, He intended that they would be

able to live with Corrine and Poland. However, six children under one roof

proved difficult for Corrine and Poland to parent, and Murphy took his siblings

to live with him.

Despite

a lot of post-war publicity, his acting career had not progressed and he had

difficulty making a living. Buck, Murphy's oldest brother, and his wife agreed

to take Nadine in, but Murphy could not find a home for Joe. He approached

James "Skipper" Cherry, a Dallas theater owner who was involved with

the Variety Clubs International Boy's Ranch, a 4,800 acres ranch near Copperas

Cove, Texas. He arranged for Joe to live at the Boy's Ranch. Reportedly, Joe

was very happy there and Murphy was able to frequently visit his brother as

well as his friend Cherry. In a 1973 interview, Cherry recalled, "He was

discouraged and somewhat despondent concerning his movie career."

Variety

Clubs International was financing “Bad Boy,” a film to help promote the

organization's work with troubled children. Cherry called Texas theater

executive Paul Short, who was producing the film, to suggest that they consider

giving Murphy a significant role in the movie. Murphy performed well in the

screen test, but the president of Allied Artists did not want to cast someone

in a major role with so little acting experience. Cherry, Short, and other

Texas theater owners decided that they wanted Murphy to play the lead or would

not finance the film. The producers agreed and Murphy's performance was

well-received by Hollywood. As a result of the film, Universal Studios signed

Murphy to a seven-year studio contract. After a few box-office hits at

Universal, the studio bosses gave Murphy increased scope in choosing his roles.

Murphy's

1949 autobiography TO HELL AND BACK became a national bestseller. The book was

ghostwritten by his friend, David "Spec" McClure, already a

professional writer. Murphy modestly described some of his most heroic

actions—without portraying himself as a hero. He did not mention any of the

many decorations he received, but praised the skills, bravery, and dedication

of the other members of his platoon. Murphy even attributed a song he had

written to "Kerrigan".

Murphy

portrayed himself in the 1955 film version of his book with the same title, “To

Hell and Back.” Murphy was initially reluctant to star in the movie, fearing it

would appear he was cashing in on his war experience. He suggested Tony Curtis

for the role. Unlike in most Hollywood films, where the same soldiers serve

throughout the movie, Murphy's comrades are killed or wounded as they were in

real life. At the film's end, Murphy is the only member of his original unit

remaining. At the ceremony where Murphy is awarded the Medal of Honor, the

ghostly images of his dead friends are depicted. This insistence on reality has

been attributed to Murphy and his desire to honor his fallen friends. Audie

Murphy's oldest son, Terry, portrayed Audie's younger brother Joseph Preston

"Joe" Murphy (at age four).

The

film grossed almost $10 million during its initial theatrical release, and at

the time became Universal Studios's biggest hit of the studio's 43-year

history. The movie is thought to have held the record as the company's

highest-grossing motion picture until 1975, when it was surpassed by Steven

Spielberg's “Jaws.”

In

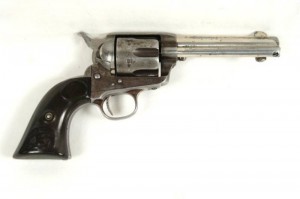

the 25 years he spent in Hollywood, Murphy made 44 feature films, 33 of them

Westerns. He played outlaws Billy the Kid, Jesse James, and Bill Doolin. His

films earned him close to $3 million in his 23 years as an actor. He also

appeared in several television shows, including the lead in the short-lived

1961 NBC western detective series “Whispering Smith,” set in Denver, Colorado.

For his contribution to the motion picture industry, Murphy has a star on the

Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1601 Vine Street.

|

| Audie Murphy in one of his many western roles |

In

addition to acting, Murphy also became successful as a country music

songwriter. He teamed up with musicians and composers including Guy Mitchell,

Jimmy Bryant, Scott Turner, Coy Ziegler, Ray and Terri Eddlemon. Murphy's songs

were recorded and released by well-known artists including Dean Martin, Eddy

Arnold, Charley Pride, Jimmy Bryant, Porter Waggoner, Jerry Wallace, Roy Clark,

and Harry Nilsson. His two biggest hits were "Shutters and Boards"

and "When the Wind Blows in Chicago".

Murphy

was reportedly plagued by insomnia, bouts of depression, and nightmares related

to his numerous battles throughout his life. His first wife, Wanda Hendrix, often

talked of his struggle with this condition, even claiming that he had held her

at gunpoint once. For a time during the mid-1960s, he became dependent on

doctor-prescribed sleeping pills called Placidyl. When he recognized that he

had become addicted to the drug, he locked himself in a motel room where he

took himself off the pills, going through withdrawal for a week.

Always

an advocate of the needs of America's military veterans, Murphy eventually

broke the taboo about publicly discussing war-related mental conditions. In an

effort to draw attention to the problems of returning Korean and Vietnam War

veterans, Murphy spoke out candidly about his own problems with PTSD, known

then and during World War II as "battle fatigue". He called on the

United States government to give increased consideration and study to the

emotional impact that combat experiences have on veterans, and to extend health

care benefits to address PTSD and other mental-health problems suffered by

returning war veterans.

Murphy

married actress Wanda Hendrix in 1949; they were divorced in 1951. He then

married former airline stewardess Pamela Archer, by whom he had two children:

Terrance Michael "Terry" Murphy (born 1952) and James Shannon

"Skipper" Murphy (born 1954). They were named for two of his most

respected friends, Terry Hunt and James "Skipper" Cherry,

respectively. Murphy became a successful actor, rancher, and businessman,

breeding and raising Quarter Horses. He owned ranches in Texas, Tucson, Arizona

and Menifee, California.

On

May 28, 1971, Murphy was killed when the private plane in which he was a

passenger crashed into Brush Mountain, near Catawba, Virginia, 20 miles west of

Roanoke, Virginia in conditions of rain, clouds/fog and zero visibility. The

pilot and four other passengers were also killed. In 1974, a large granite

marker was erected near the crash site. On June 7, 1971, Murphy was buried with

full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. A special flagstone

walkway was later constructed to accommodate the large number of people who

visit to pay their respects. It is the second most-visited grave site, after

that of President John F. Kennedy.

The

headstones of Medal of Honor recipients buried at Arlington National Cemetery

are normally decorated in gold leaf. Murphy previously requested that his stone

remain plain and inconspicuous, like that of an ordinary soldier. An unknown

person maintains a small American flag next to his engraved Government-issue

headstone, which reads as follows:

Audie

L. Murphy, Texas. Major, Infantry, World War II. June 20, 1924 to May 28, 1971.

Medal of Honor, DSC, SS & OLC, LM, BSM & OLC, PH & 2 OLC.

Murphy’s

diverse honors are far too numerous to list here so I’ll mention only those in

the county of his birth, Hunt County, Texas. From the mid-1990s through the present, an annual

celebration of Murphy and other veterans in all branches of service has been

held on the weekend closest to Murphy's birthday at the American Cotton Museum,

renamed The Audie Murphy/American Cotton Museum (in Greenville, Texas), which

houses a large collection of Murphy memorabilia and personal items. His statue

stands in front of the museum.

A monument in his honor stands in Celeste, the

small town where he attended school for five years. Farmersville also claims

Audie Murphy, since that is where his sister Corinne lived and the address on

his draft information.

Highway 69 from Greenville to Fannin County is the Audie

Murphy Memorial Highway, and Highway 34 crosses the railroad tracks in

Greenville on the Audie Murphy Memorial Overpass.

Mark your calendar for the annual

Audie Murphy Day celebration in Farmersville, Texas with a Military flyover at

10 am followed by parade downtown and program under the Onion Shed.

|

| Audie Murphy statue at Greenville, Texas Museum |

As

we remember those who have gone before us this weekend, let’s remember soldiers

like Audie Leon Murphy and his comrades.

Thanks

to Wikipedia, www.audiemurphy.com, and the Chambers of Commerce of Greenville,

Celeste, and Farmersville, Texas.