By Andrea Downing

With the on-going dispute as to whether certain Dr. Seuss books should be removed from shelves due to their outdated views and racism, I thought I would have a look at banned books, both past and present. While the Seuss books were not strictly banned, they have been removed from libraries, and publication of the notorious six has been stopped. What happens when freedom of speech, and the inherent writing, conflict with the mores of the time?

The Puritans, of course, were masters of telling folks what they could and could not read and write. The first known banned book in America was Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan published in 1637. It encouraged readers to love Native Americans and satirized the Puritans. In the eighteenth century, while America still strained under the yoke of Britain, Defoe’s Moll Flanders and Roxana: the Fortunate Mistress, as well as the perhaps more infamous Fanny Hill by John Cleland, met the censor’s ax. Fanny Hill bears the dubious distinction of being the last book to be banned throughout the USA. While the dime novels of the nineteenth century may have caused an outrage or two, increased literacy, and hence literary output, seems to have led to an accepted form of censorship. Expurgation and the accompanying bowdlerization of numerous books was acknowledged as protecting public virtue and decency. Even Shakespeare did not elude cuts. Perhaps the most famous of nineteenth century banned books is The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

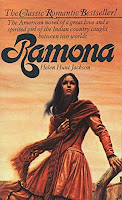

First banned in MA in 1885 as “trash and suitable only for the slums,” Huck Finn has been repeatedly challenged, usually on the basis on the N—word, appearing over 200 times in the book. In the 1950s, the NAACP began challenging the book as racist because of its portrayal of the slave Jim and the repeated use of racially pejorative terms—a conflict that has repeatedly harassed To Kill A Mockingbird as well. During his lifetime, Twain aka Samuel Clemens, simply saw the controversies surrounding his book as excellent fodder for promotion. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin is occasionally credited with having started the Civil War but, although it may have been difficult to purchase in southern states, it was never officially banned. I’m sure Congress might have liked to ban Helen Hunt Jackson’s A Century of Dishonor as well as Ramona, both of which deal with the treatment of Native Americans, especially by the federal government, but that didn’t happen either.

However, in the twentieth century, guardians of public morality became rife. Almost everything Theodore Dreiser wrote was either challenged or banned: Sister Carrie, Genius, and An American Tragedy were all held in check by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, The Western Society for the Prevention of Vice, and the Boston District Attorney. But it was James Joyce’s Ulysses, considered by many one of the great masterpieces of modern literature, that really brought up a host of questions as to what is acceptable as freedom of speech and what is not: what has literary merit and what is pornographic? It is a question that bears heavily on free speech, under the

jurisdiction of individual states, the federal government only being able to intervene when items are passed between states. The federal government passed an obscenity law in 1873 when the Supreme Court decided that pornography/obscenity was not protected by the First Amendment, yet this still leaves the question open as to what is obscene. The toing and froing over Ulysses took some fifteen years internationally to finally be settled in a NY court of law when it was decided that Joyce’s purpose, despite several sexually explicit scenes, was not pornographic. I can only wonder if E.L. James can truly stand up to such a test. Oh, but I forget: today we have ‘erotic’ literature…

The other famous court case of the twentieth century was, of course, Lady Chatterly’s Lover. I can well remember the girlish giggles accompanying “discussion” of who had a copy of the book and where we might gather to read passages away from the prying eyes of teachers and parents. Chatterly and Tropic of Cancer, of course. Chatterly had been banned for both its coarse language and explicit scenes of a sexual nature, but in 1959 the ban of this, along with Fanny Hill and Tropic of Cancer, was overturned when the court found it had merit of a literary nature. As an aside, let me say that the case was then taken up in the UK the following year, where the judge asked the famous question, “would you want your wife and servants to read this book?” After three hours of deliberation in Her Majesty’s Court, the answer was, “yes.”

Nowadays, the predominant challenge to books is that they are unsuitable for their age group, having too much violence, too much sex for their age group, containing controversial issues, offensive language, promoting homosexuality, containing drugs/alcohol/smoking/gambling, being socially offensive, containing nudity, and just about any other ‘vice’ you can think of. Recently banned books include The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, by Sherman Alexie, which work contains “cultural insensitivity” and “depictions of bullying,” the Harry Potter series, Of Mice and Men, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, The Color Purple, Catcher in the Rye, To Kill A Mockingbird, Snow Falling on Cedars, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Kite Runner and, yes, Huck Finn. And Tango Makes Three, a true story about same-sex penguins who were given an egg to raise after building a nest together and trying to raise a ‘rock’, has been challenged numerous times as promoting homosexuality. I wonder if the author ever thought twice about not writing this incredible story?

This year’s list continues to include Huck as well as To Kill a Mockingbird. There is also The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison (about a Black girl who prays every day for blond hair and blue eyes), The Cay by Theodore Taylor (about a blinded 11-year-old boy who must rely on a West Indian man), Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred Taylor (about racisim during the Great Depression and Jim Crow era), The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas (banned due to drug use and explicit language), George by Alex Gino (with a transgender lead character), and This One Summer by Mariko Tamaki (banned for LGBTQIA+ characters, drug use, and profanity, scenes of a sexually explicit nature).

Different parents, different schools and libraries, different states will each see these books in a very different light: do they enlighten or do they incite vice, do they educate or instruct immorality? And where does freedom of speech stop and inculcating evils—if such they be—begin?

Parts of this post appeared on my blog in November, 2015, titled “So You Think We Have Freedom of Speech?”