Since March is Women in History month, I thought I'd share a little info about a woman many don't know served as Oregon's governor before women had the right to vote.

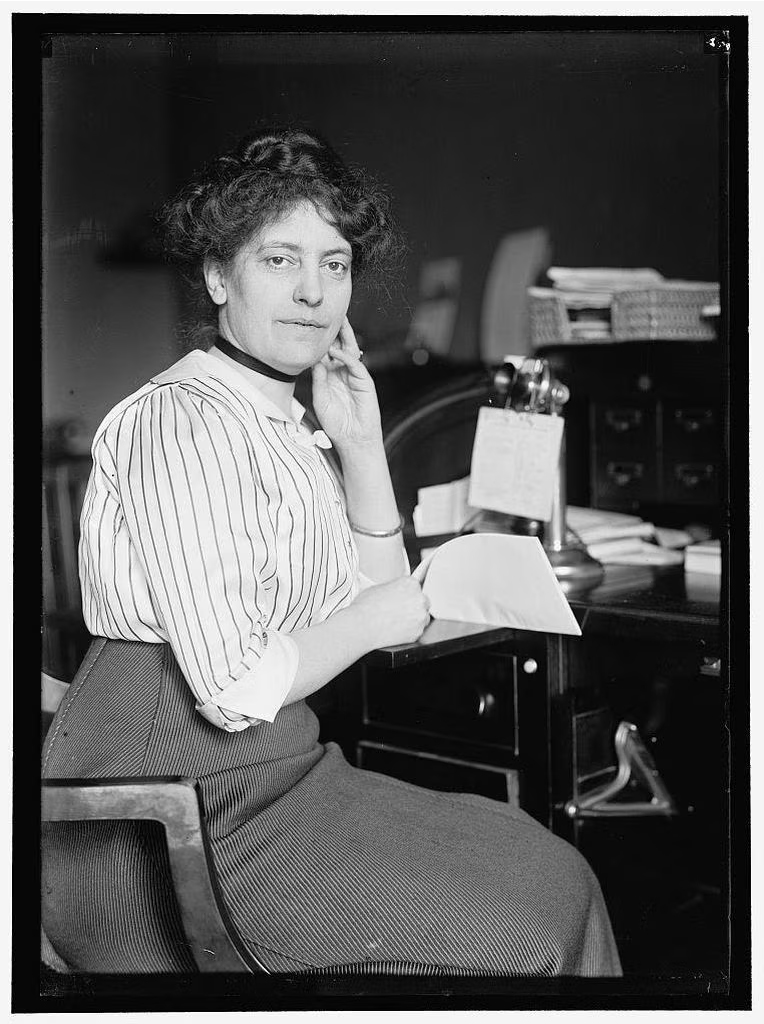

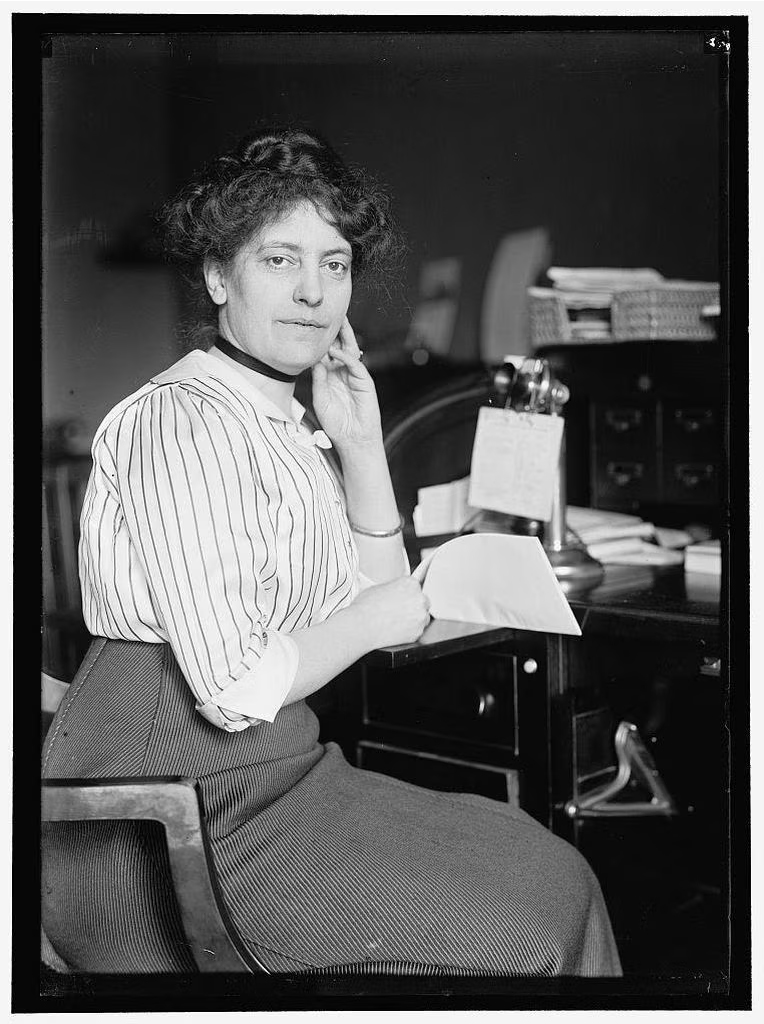

Carrie Bertha Shelton is a woman all but forgotten by history.

Library of Congress

For a weekend in 1909, she was the first female governor in the United States.

Carrie Bertha Skiff was born October 3, 1876 in Union County, Oregon, the fourth of Willis and Mary Skiff’s six children.

Accounts report her childhood as one of comfort. Her father was a Union County and Union city official before transitioning into the role of business man.

However, life changed for Carrie in 1886 when her father disappeared. He was on a business trip to North Powder, Oregon, and was last seen sitting outside the town's hotel, awaiting the midnight train to return home. When he failed to arrival, his disappearance sparked an investigation. The case was never solved. Carrie's mother passed away a few years later, leaving the children orphaned. Carrie and two of her siblings went to live with their older brother, Orin, and his wife. In 1889, Carrie, and her sister Mabel become wards of Union County Judge John W. Shelton, who was one of the leaders looking into the mystery if Willis Skiff's disappearance.

In 1892, with his wife away visiting family in California, John Shelton obtained a divorce before heading off to Weiser, Idaho with Carrie. They wed just two weeks after her 16th birthday and moved to the Portland area. Less than two years after their marriage, Carrie was a widow.

She started a career as a stenographer at the Portland law firm of Chamberlain and Thomas in 1895. There she began working with George Chamberlain, a powerful attorney.

A quick learner with a talent for the technical terms of the law, Chamberlain took her under his wing and gave her responsibilities not usually afforded to stenographers.

When Chamberlain was elected to the Multnomah County district attorney’s office in 1900, he took her with him. There, she enhanced her legal knowledge by helping draft indictments.

At the ripe old age of 25, Shelton joined Chamberlain in Salem when he was elected governor. Chamberlain served two tenures in the governor’s office, and at some point Shelton was promoted from stenographer to his personal secretary.

In 1909, Chamberlain was elected to represent Oregon in the U.S. Senate. His term as governor would end March 1, but all freshmen senators were slated to be sown in March 4 in Washington D.C. If Chamberlin stayed through the end of February, he'd be sworn in late and all the other members of the freshman senate class would have seniority over him. That would never, ever do.

Ordinarily, the incoming governor would have assumed his post a few days early, but Frank W. Benson was too ill to step up to the plate. At that time, Oregon law stated in the event of the chief executive’s death the Secretary of State should become governor. In the absence of the governor— whether due to illness, travel out of state, etc.— his private secretary would become acting head of state.

And Chamberlin's private secretary was Carrie Shelton, who had started using the name Caralyn to sound more professional.

At 9:15 a.m. on the morning of Saturday, Feb. 27, 1909, Shelton assumed the role of the acting governor — becoming the nation’s first female governor. For a weekend, a woman who couldn’t legally cast a ballot possessed the power to issue pardons, veto bills and sign executive orders.

For 48 hours and 55 minutes, Carrie Shelton was the acting head of Oregon's government. Although she couldn't legally cast a ballot (it would be a few more years before women had the right to vote in Oregon) she held the power to issue pardons, veto bills and sign executive orders.

She did none of those things, but how sad she is never mentioned on lists of historical women in America.

She was quoted as saying, "I want to fill the governor's shoes, and he really has a small foot. I fear the principal trouble will be in trying to fill his hat." What a sense of humor!

The following Monday, at a few minutes past ten in the morning, her time in office was over. Benson was formally sworn in as governor.

Headlines across the state had a heyday with the news, though.

“Oregon Has Today a Woman Governor” read the headline of the Daily Capital Journal (Salem) on February 27, 1909 with a subhead that stated, "Mrs. C. B. Shelton First Woman to Govern Any State."

"Has Three Governors In Three Days," the front page of The Daily Capital Journal stated on March 1, 1909. "Oregon Holds The World's Record For Changing Rulers. Secretary of State Benson is today the third governor that Oregon has had in the last three days."

Not long after being relieved of her duties as acting governor, Shelton boarded a train bound for Washington, D.C., joining now-Sen. Chamberlain once again as his personal secretary. She oversaw his staff of clerks. By 1914, she also served in the role of the clerk to the Senate Committee on Military Affairs, of which Chamberlain was the ranking member. Shelton remained with Chamberlain when he joined the United States Shipping Board in 1921, serving as his personal secretary until he resigned in 1923. He returned to private law in the D.C. area and Shelton continued working alongside Chamberlain through the death of his wife, Sallie, in 1925. When Chamberlain suffered from a paralytic stroke at age 72, Carrie remained with him.

Shelton and Chamberlain wed in Norfolk, Virginia on July 12, 1926. George Chamberlain died after a brief illness on July 9, 1928, three days shy of the couple’s second wedding anniversary.

Carrie returned home to Oregon. She lived out her remaining years between Union County and Salem. She died on Feb. 3, 1936, at age 59 and her memorable moments as the first female governor in America were all but forgotten.

USA Today Bestselling Author Shanna Hatfield grew up on a farm where her childhood brimmed with sunshine, hay fever, and an ongoing supply of learning experiences.

Shanna creates character-driven romances with realistic heroes and heroines. Her historical westerns have been described as “reminiscent of the era captured by Bonanza and The Virginian” while her contemporary works have been called “laugh-out-loud funny, and a little heart-pumping sexy without being explicit in any way.”

When this award-winning author isn’t writing or testing out new recipes (she loves to bake!), Shanna hangs out at home in the Pacific Northwest with her beloved husband, better known as Captain Cavedweller.

.png)