What's the inspiration for my stories? History, loss, hope, adventure, love, and quite often horses.

Last month I shared my Story Inspiration page (a page that I've included in the back of all of my books) for my first book, Between Heaven & Hell. Today I'm sharing the Story Inspiration page for the sequel to that story...

FOLLOWING FAITH

Story Inspiration page ~ from the back of the book

Following Faith came to life after I was asked to write a short story for the historical romance anthology Journey of the Heart featuring forms of Old West transportation.

I’d always planned to give Hannah’s brother, Eagle Feather (first seen in Between Heaven & Hell) his own story. Oregon became the setting since that was where Hannah had settled, and I wanted his path to reconnect with Hannah’s.

Next came the decision of what transportation to use. Train, boat, stagecoach, wagon, or just plain old horseback—which I never find plain when every horse is unique. A childhood memory of a very unique horse and a much-loved book sprang to mind.

San Domingo, the Medicine Hat Stallion first published in 1972 by Marguerite Henry (with illustrations by Robert Lougheed) was re-published as Peter Lundy and the Medicine Hat Stallion in 1972 (when it became a TV movie). Set in Pony Express-era Wyoming, the story’s core is the bond between a boy and a pinto horse with a very specific and rare color pattern—a mostly white body, neck, and head with a darker color that covers the top of the horse’s head and ears like a bonnet or a hat.

Native legend said such a horse held the medicine to protect its rider from harm. The horse was greatly coveted and often stolen by those who wished to safeguard their—or a loved one’s—life.

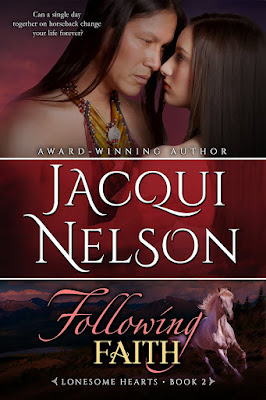

FOLLOWING FAITH

Can a single day together on horseback change your life forever?

Labeled a harlot and expelled from a remote logging camp and her only employment teaching children, Faith Featherby embarks on a journey to return a stolen spirit horse to the little girl whose photograph she found hidden in the horse’s riding blanket.

Orphaned young and stifled by a lifelong shyness, Faith has only her education as a schoolmistress and her memories of her mother’s stories. She’s not an experienced rider, but a Medicine Hat horse—alleged to have the sacred power to protect its rider—might be her best hope for surviving the wilderness... until an Osage warrior rides out of the mist.

Scarred by a brutal past, the warrior challenges Faith to follow a new path where belief in yourself and your partner, be they horse or man, can lead to a triumph of the heart.

Follow a path. Find a partner. Fight for a future together.

Click here to read an excerpt on my website.

~ * ~