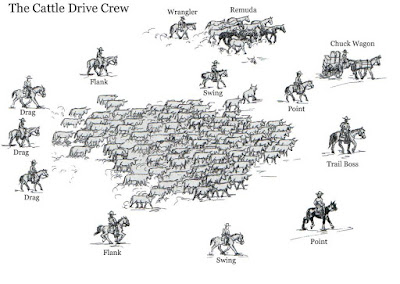

These days, Kimball Bend is an Army Corps. of Engineers park along Highway 174 in Bosque County, Texas, close to the Brazos River bridge. However, in cattle drive days it’s where drovers herded their longhorn charges across the Brazos on their way up the Chisholm Trail. In the late 1860s there was also a ferry at this location.

Kimball Bend seen from Bridge across the Brazos

When researching for Dashing Irish a few years ago, I learned that Red River Station, the place where cattle drives crossed the Red River on their way north, ca. 1874, was also at a bend in the river. Preston Bend was yet another famous cattle crossing on the earlier Shawnee Cattle Trail, located farther east on the Red.

Were all these crossings at river bends mere coincidence? Of course not. Trail drivers chose such crossing points because the river current helped them shepherd their cattle toward the opposite bank as it rounded the bend.

At the crossing of Big Elk Creek in Oklahoma, there’s a horseshoe bend in the creek where drovers led their steers into the water. The bend acted almost like a corral or cattle chute and helped to keep the herd moving smoothly. Those cowboys were no fools!

Dashing Irish just received a 4 1/2 star review from InD’Tale Magazine. I’m thrilled! http://www.indtale.com/magazine/2013/september/#?page=80

Now here’s an excerpt illustrating how rough a river crossing could be.

At least half the herd was across now, and most of the men were in the water, Tye included. Minutes ago, Lil had seen him driving cattle into the river. He was supposed to bring up the rear with Kirby, but he must have traded places with Dewey, because the black cowboy wasn’t in sight. She knew why Tye had done it; he wanted to keep an eye on her. She was certain of it because she’d caught him watching her with a worried look on his face.

He was as bad as her father. She wanted to shake him. All cut up like he was, he was the one who had no business in a raging river, not her.

She spotted him near the south bank. From the way he moved as he swatted a wayward longhorn into line, you’d think there wasn’t a thing wrong with him. The dumb galoot! Chic would likely have to stitch him up all over again. She shook her head in exasperation and turned her attention to the cattle. A moment later, she was nudging a steer back in the right direction when all hell broke loose.

“Lil, look out! Tree comin’!” Tye shouted.

Jerking her head around, Lil saw an uprooted stump headed straight for her. She gasped and kicked Major hard. He plunged forward just in time to avoid being rammed by the snag.

Several longhorns weren’t so lucky. The tree stump barreled into them with a sickening crunch of horn and bone. A few sank and were carried away along with the stump; others bawled in terror as they collided with their neighbors. Panicked animals milled in all directions. More went under, and some didn’t resurface.

It was move fast or lose dozens of cattle. Unmindful of danger, Lil headed Major into the tangle of bovine bodies. Neil, Jack, and the others did likewise, yelling and lashing out with their ropes as they fought to stop the mêlée. Luckily, they were over the sandbar; that made things a little easier. After several moments, all the steers were finally headed north again.

Lil glanced around for Tye. He’d swum the big roan he rode out to help. Bobbing in the water about twenty yards away, he met her gaze, and a relieved look spread across his face. She was just as relieved to see him safe. He smiled and waved, and she returned the gesture. Then she noticed how sluggishly Major was moving.

“Sorry, boy, I should’ve cut you loose to rest,” she said, patting his neck. “Let’s head for shore.”

They’d just left the sandbar behind when a wild-eyed sabina steer swerved out of line toward them. Lil tried to guide Major out of the way again, but he couldn’t react fast enough. The longhorn hooked him in the shoulder with a sharp horn. Screaming in pain, the chestnut pitched over sideways.

Lil cried out and heard Tye shout her name; then her head went under. Water filled her nose and throat. She kicked frantically, managing to break free of the thrashing horse and propel herself upward. She broke the surface coughing, fighting for air.

Major managed to right himself, and Lil grabbed for him. She missed as the tricky current carried him away. He kicked feebly; she was terrified neither of them would make it.

“Lil, I’m coming!” Tye cried, her terror slamming into him, doubling his fear for her as he forced his horse between two thrashing steers that blocked his way.

Lil twisted in the water to look at him. Then a wave slapped her in the face, dragging her under again. Tye held his breath the instant she did, experiencing her fear and desperate will to live as she fought her way upward amid the thrashing longhorns. She surfaced and he gulped air along with her, then silently cheered when she grabbed onto the horn of a passing steer. Its owner bellowed and tried to shake her off, but she clamped an arm around his thick neck and clung to him.

“Hang on, Lily!” Tye shouted, heart beating like a drum.

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B0069HLDJU (Kindle)

http://www.amazon.com/dp/1470004003 (paperback)

http://tinyurl.com/lk8w55d (Nook)